The Norwegian Developers Conference 2014 just ended and they have already posted all the videos of all the talks that were given this past week. Two talks in particular caught my attention.

The first is a talk about Railway Oriented Programming (an interesting technique to manage error handling in functional languages) by Scott Wlaschin. Because I don't actually use functional languages I won't comment any further about this talk and I will limit myself to bringing it to your attention, just in case you also might be intrigued by the way Scott uses the railway methaphore to illustrate a concept that might be otherwise difficult to explain.

The second talk is Zone out, check in, move on by Mark Seemann. I hold Mark in high regard -- he is a brilliant .NET architect, a prolific blog writer, and the author of Dependency Injection in .NET, Amazon number one best seller in the Software Testing category. If you have one hour of time to spare, I highly recommend watching the entire talk. If not, I asked Mark permission to summarize here some key ideas that particularly resonated with me.

Most programmers love to be in the zone as much as possible. This is what makes developing an enjoyable experience. However, no matter if you work in an office or if, like me and Mark, you have the luxury of being able to work from home, the reality is often one of interruptions. Interruptions are not only unavoidable, but they tend to increase in number when a developer grows into a senior developer, first, and then into a lead developer.

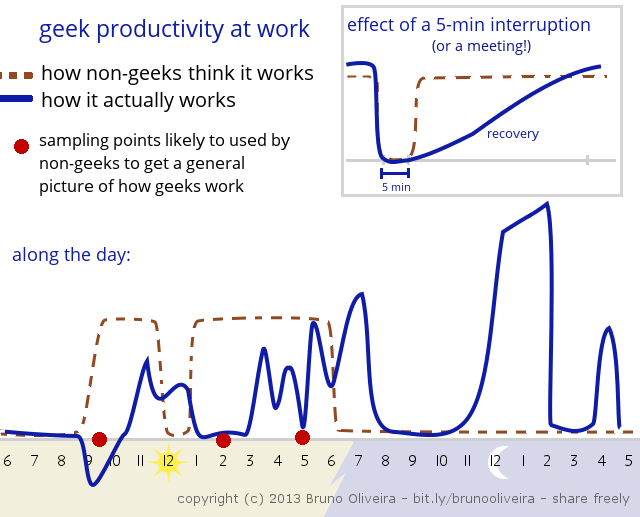

Bruno Oliveira posted a fun diagram which depicts the productivity at work of a developer along the day:

Humor aside, the smaller diagram in the top-right, which shows the effect of a 5-minute interruption (or a meeting) on productivity, turns out to be surprisingly accurate. First of all, we need to better understand why it takes so long (15-20 minutes) to go back to the same level of productivity. After all, in a lot of different professions this does not seem to happen. When I am at the veterinarian's office for my dog's check-up, for example, the vet gets interrupted at least half-a-dozen times during the 30-minute long appointment, yet he seems to handle those interruptions really well and his recovery time is just a few seconds.

The reality is that, quite ironically, developers tend to be very bad at multitasking. This is because when we write code we need to constantly keep in our heads a mental model of the problem at hand (i.e. the classes involved, the relationships between them, the 'stacktrace' of the code execution, corner cases, etc.). In essence, while developing code our brains simulate the work of an interpreter: we read source code, we build a model of what we think that code will be doing when executed, and we execute this model in our head, line by line. Whenever a distraction comes along, during the post-distraction recovery phase we find ourselves retracing our steps by reading again bits and pieces of source code and rebuilding that model in our head. This takes time and it is also a tiring process - which means that every recovery phase will take a bit longer than the previous one.

Next, Mark goes over a few different strategies to help us cope with these interruptions. Since interruptions are often unavoidable, he focuses on a few different strategies that can help us shortening the recovery phase, since after all, it is only after the recovery phase is completed that we are able to get back in the zone, the magical place where developing becomes enjoyable again. Out of all the strategies Mark mentioned in his talk, I'd like to focus on two, which I found particularly interesting.

1. Use a smaller screen

This might seem counter-intuitive especially since as programmers we have spent the last few years asking our managers/bosses to provide us with more and bigger screens, claiming that having more screens would allow us to become more productive. The reality, though, is that more screens inevitably provide us with more distractions (incoming emails, Lync, Skype, too many documents open, too many windows open, etc.). Mark says that a smaller screen (in the video Mark shows a screenshot of his 13" screen laptop during a coding session) motivated him to decompose the code that he writes in reasonably sized parts that allow him to keep everything under control by just looking at the screen.

Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand. [Martin Fowler, 2008]

Writing good code obviously requires creative thinking, and, as with many other creative endeavors, introducing artificial constraints in the creative process often is enough to spark creativity.

It makes you think out of the box because you are being put into the box -- says Mark.

The size of the screen though really doesn't matter (so if you like having two or three monitors, go ahead, and keep doing it). What matters is the fact that by limiting the size of the screen he found himself more and more applying the "divide and conqueer" strategy to his work. Instead of working on very large scale systems in their entirety, he started decomposing the systems into smaller loosely coupled units which obviously, by their intrinsic nature of being smaller, both in size and in complexity, help shortening the distraction recovery time -- one more valid reason that adds itself to all the other advantages of decomposing large solutions into smaller parts.

2. Use a Distributed Version Control System (DVCS)

We tend to think of a version control system as a way of saving, once we are done, all the code that was developed for a particular bug / feature, into a safe location. The name of Visual Source Safe highlighted this particular aspect of the nature of a VCS.

Using a distributed VCS, instead of a centralized one (such as TFS), enables the developer to switch context painlessly. For exmaple, to see the state of the code in a particular branch (i.e. feature-42), in git takes just one command:

git checkout feature-42

Almost instantly, because everything happens locally on the developer's machine, with absolutely no network connectivity needed, the working directory will be updated with the files from branch feature-42. Switching back to the master branch, can be done with a similar command:

git checkout master

Creating a new branch (i.e. feature-43), also requires another simple command:

git checkout -b feature-43

Remember, this is a local branch, no network is involved, everything happens just on the local machine, which make the branch creation a sub-second operation.

Working in branches is not an evil thing. The people that are scared of branches think of merge conflicts (which can admittedly be hell). But merge conflicts are not triggered by the mere acting of branching.

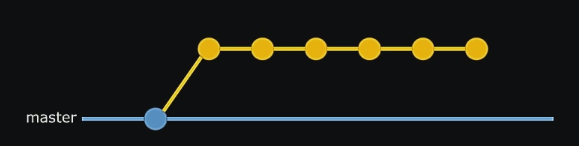

Instead, working in branches enables you to explore fearlessly. You have an idea, you simply create a new branch, and you start committing to it, as often as every few minutes (Mark actually suggest to keep it really short: "never more than 5 minutes from a check-in"):

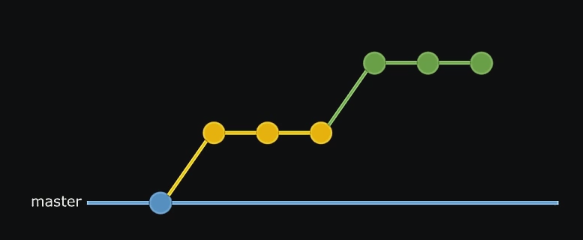

If I figure that, for example, the last few commits I made were a mistake, but the initial idea of this branch was good, I can rollback the last commits, and then try something different:

When you think that what you have is good, you merge back to the master branch:

git checkout master

git merge feature-43

All of this, by the distributed nature of git, happens on your local machine. No one else sees it. Once you merge to the master branch, you can then push to the shared repository so that everyone else in the team can see your code. This keeps your source control history clean and keeps the number of commits down.

Never be more than five minutes from a check-in

Every time you make a change to your code that leaves the system in a state that is as good as it was before, or better (i.e. not worse), just check the change in.

The more commits you have, the larger number of options you have when rolling back if necessary (every check-in gives you a snapshot of the code to which you can easily go back -- having more check-ins is like having more undo levels in an application).

Integrate often

Branching is not evil, but merging is.

Merge conflicts are nothing else than concurrency issue. It means two or more developers have been working on the same piece of source code in between two merges. If there were no concurrent work being done on the same file, there would not be a merge conflict. In other systems to resolve concurrency issues the normal approach is to make sure that transactions happen as fast as possible.

This translates into making sure to merge as often as possible. This minimizes the chance of having a merge conflict when merging because it reduces the window of time during which a piece of source code risks to be modified by more than one developer.

A branch that gets older than a couple of hours should be merged.

Handling incomplete branches

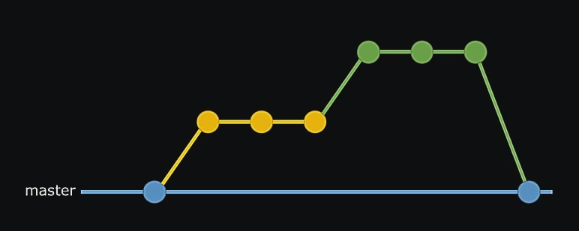

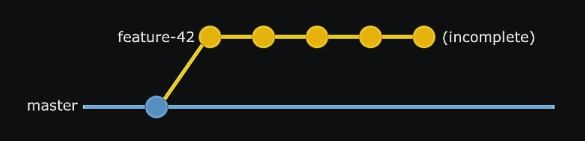

Often it happens that a feature (i.e. feature-42) is not completed within a few hours and you understand that it will take much longer to be completed:

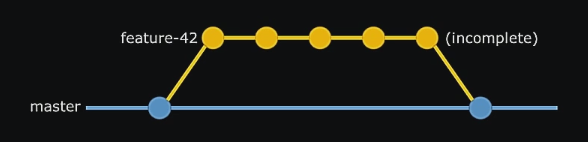

Most people would leave the branch there dangling waiting for the branch to be completed, but, in most cases, the best way to handle this scenario is simply to integrate the feature anyways into the master branch:

This is because most often:

The cost of having merge conflicts is bigger than the cost of having incomplete features in the master branch.

And if you don't like to have incompleted features in the master branch, all you have to do is to use feature toggles.

We don't know how to minimize the cost of merge conflicts, but we know how to minimize the cost of having incomplete features in the master branch, by using feature toggles.

Feature toggles can be configuration files, or complex boolean expressions in code that determine whether a feature should be turned on or off within a particular environment (i.e. this will allow a particular developer to have a feature enable on a machine, and in the QA system, but not in production, for example). A side effect of using feature toggles is that your code will need to be modular enough to be "wrappable" by the toggles -- which inevitably brings us back to the advantages of writing loosely coupled code.

More about Feature Toggles

Feature Toggles were discussed also by Martin Fowler back in 2010. Here is an excerpt taken from that article:

One of the most common arguments in favor of FeatureBranch is that it provides a mechanism for pending features that take longer than a single release cycle. Imagine you are releasing into production every two weeks, but need to build a feature that's going to take three months to complete. How do you use Continuous Integration to keep everyone working on the mainline without revealing a half-implemented feature on your releases? We run into this issue quite a lot and feature toggles are a handy tool to deal with it. The basic idea is to have a configuration file that defines a bunch of toggles for various features you have pending. The running application then uses these toggles in order to decide whether or not to show the new feature.

For more info, read Martin's article.

Feature toggles (aka feature flags or feature flippers) provide an alternative to maintaining multiple source code branches and have been used for years by many large websites. Let's take a look at a few notable examples.

Here is an example from Flickr published back in 2009.

Flickr is somewhat unique in that it uses a code repository with no branches; everything is checked into head, and head is pushed to production several times a day. This works well for bug fixes that we want to go out immediately, but presents a problem when we’re working on a new feature that takes several months to complete. How do we solve that problem? With flags and flippers!

At Google they call them conditional features and they have been using them, for example, when developing the new Gmail look, back in 2011.

This is our ability to make changes to the Gmail code that get deployed, but not executed. You can think of it as a lot of if-statements around the new code that get enabled when the conditional feature is on. The conditional feature flag itself is set outside of the deployed code. These flags can be set in various ways: as a percentage of overall users (if we want to rollout a feature slowly), for Googlers only (if we want to use a new feature internally), for individuals (if we want to give users early access to a features) and in many other ways. In short, conditional features allow us to update our production systems separately from releasing new features. This way, Gmail developers can make changes, but don’t have to worry about their unfinished changes being released before they are ready.

In my opinion the most interesting aspect of conditional features is the fact that they are not just switches turned on or off by a static configuration file (or similar mean). In fact complex logic, based for example on environment, time and/or user base, can be used to decide whether a feature should be shown or not. This even allows testing a new feature on a subset of end users and start collecting important usage information before deploying the new feature to the whole the users.

I would like to end this quite long blog post first of all by thanking Mark for allowing me to summarize salient parts of his interesting talk.

And I would like to leave you with a note about an interesting trend that seems to be very related to this topic: contemplative computing.

At the end of last year, JWT, one of the largest agency network in the world, published the yearly list of 100 things to watch in 2014, and Contemplative Computing was one of them. Contemplative computing is about learning to use information technologies in ways that help you be more focused and mindful, and protect you from being perpetually distracted.

Contemplative computing may sound like an oxymoron, but it's really quite simple. It's about how to use information technologies and social media so they're not endlessly distracting and demanding, but instead help us be more mindful, focused and creative.

If you want to learn more about contemplative computing, you can either read Alex Soojung-Kim Pang's book "The Distraction Addiction", visit the author's blog here or watch his talk at Lift11 in Marseille.